Bloat

Bloat is a life-threatening emergency that affects dogs in the prime of life. The mortality rate for gastric volvulus approaches 50 percent. Early recognition and treatment are the keys to survival.

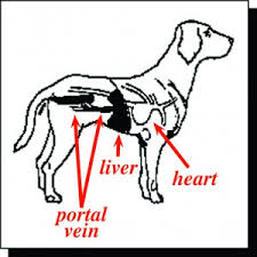

Bloat can occur in any dog at any age, but typically occurs in middle-aged to older dogs. There may be a familial association. Large-breed dogs with deep chests are anatomically predisposed. Bloat develops suddenly, usually in a healthy, active dog. The dog may have just eaten a large meal, exercised vigorously before or after eating, or drank a large amount of water immediately after eating.

Signs of Bloat

The classic signs of bloat are restlessness and pacing, salivation, retching, unproductive attempts to vomit, and enlargement of the abdomen. The dog may whine or groan when you press on his belly. Thumping the abdomen produces a hollow sound. Unfortunately, not all cases of bloat present with typical signs. In early bloat the dog may not appear distended, but the abdomen usually feels slightly tight. The dog appears lethargic, obviously uncomfortable, walks in a stiff-legged fashion, hangs his head, but may not look extremely anxious or distressed. Early on it is not possible to distinguish dilatation from volvulus. Late signs (those of impending shock) include pale gums and tongue, delayed capillary refill time, rapid heart rate, weak pulse, rapid and labored breathing, weakness, and collapse. If the dog is able to belch or vomit, quite likely the problem is not due to a volvulus, but this can only be determined by veterinary examination.

Treating Bloat

In all cases where there is the slightest suspicion of bloat, take your dog to a veterinary hospital immediately. Time is of the essence. Gastric dilatation without torsion or volvulus is relieved by passing a long rubber or plastic tube through the dog’s mouth into the stomach. This is also the quickest way to confirm a diagnosis of bloat. As the tube enters the dog’s stomach, there should be a rush of air and fluid from the tube, bringing relief. The stomach is then washed out. The dog should not be allowed to eat or drink for the next 36 hours, and will need to be supported with intravenous fluids. If symptoms do not return, the diet can be gradually restored.

A diagnosis of dilatation or volvulus is best confirmed by X-rays of the abdomen. Dogs with simple dilatation have a large volume of gas in the stomach, but the gas pattern is normal. Dogs with volvulus have a “double bubble” gas pattern on the X-ray, with gas in two sections separated by the twisted tissue.

If the dog has a volvulus, emergency surgery is required as soon as the dog is able to tolerate the anaesthesia. The goals are to reposition the stomach and spleen, or to remove the spleen and part of the stomach if these organs have undergone necrosis.

Preventing Bloat

Dogs who respond to no surgical treatment have a 70 percent chance of having another episode of bloat. Some of these episodes can be prevented by following these practices:

Divide the day’s ration into three equal meals, spaced well apart.

Do not feed your dog from a raised food bowl.

Avoid feeding dry dog food that has fat among the first four ingredients listed on the label.

Avoid foods that contain citric acid.

Restrict access to water for one hour before and after meals.

Never let your dog drink a large amount of water all at once.

Avoid strenuous exercise on a full stomach.

Bloat is a life-threatening emergency that affects dogs in the prime of life. The mortality rate for gastric volvulus approaches 50 percent. Early recognition and treatment are the keys to survival.

Bloat can occur in any dog at any age, but typically occurs in middle-aged to older dogs. There may be a familial association. Large-breed dogs with deep chests are anatomically predisposed. Bloat develops suddenly, usually in a healthy, active dog. The dog may have just eaten a large meal, exercised vigorously before or after eating, or drank a large amount of water immediately after eating.

Signs of Bloat

The classic signs of bloat are restlessness and pacing, salivation, retching, unproductive attempts to vomit, and enlargement of the abdomen. The dog may whine or groan when you press on his belly. Thumping the abdomen produces a hollow sound. Unfortunately, not all cases of bloat present with typical signs. In early bloat the dog may not appear distended, but the abdomen usually feels slightly tight. The dog appears lethargic, obviously uncomfortable, walks in a stiff-legged fashion, hangs his head, but may not look extremely anxious or distressed. Early on it is not possible to distinguish dilatation from volvulus. Late signs (those of impending shock) include pale gums and tongue, delayed capillary refill time, rapid heart rate, weak pulse, rapid and labored breathing, weakness, and collapse. If the dog is able to belch or vomit, quite likely the problem is not due to a volvulus, but this can only be determined by veterinary examination.

Treating Bloat

In all cases where there is the slightest suspicion of bloat, take your dog to a veterinary hospital immediately. Time is of the essence. Gastric dilatation without torsion or volvulus is relieved by passing a long rubber or plastic tube through the dog’s mouth into the stomach. This is also the quickest way to confirm a diagnosis of bloat. As the tube enters the dog’s stomach, there should be a rush of air and fluid from the tube, bringing relief. The stomach is then washed out. The dog should not be allowed to eat or drink for the next 36 hours, and will need to be supported with intravenous fluids. If symptoms do not return, the diet can be gradually restored.

A diagnosis of dilatation or volvulus is best confirmed by X-rays of the abdomen. Dogs with simple dilatation have a large volume of gas in the stomach, but the gas pattern is normal. Dogs with volvulus have a “double bubble” gas pattern on the X-ray, with gas in two sections separated by the twisted tissue.

If the dog has a volvulus, emergency surgery is required as soon as the dog is able to tolerate the anaesthesia. The goals are to reposition the stomach and spleen, or to remove the spleen and part of the stomach if these organs have undergone necrosis.

Preventing Bloat

Dogs who respond to no surgical treatment have a 70 percent chance of having another episode of bloat. Some of these episodes can be prevented by following these practices:

Divide the day’s ration into three equal meals, spaced well apart.

Do not feed your dog from a raised food bowl.

Avoid feeding dry dog food that has fat among the first four ingredients listed on the label.

Avoid foods that contain citric acid.

Restrict access to water for one hour before and after meals.

Never let your dog drink a large amount of water all at once.

Avoid strenuous exercise on a full stomach.