The Domestication and Origin of the Modern Day Dog

Origin

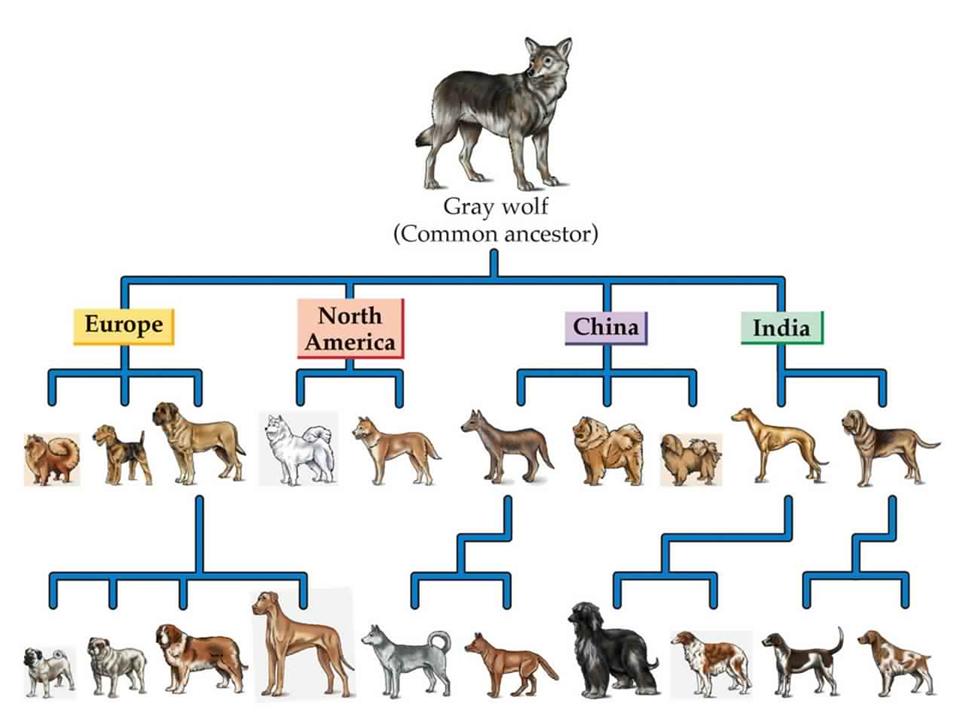

The origin of the domestic dog began with the domestication of the Grey Wolf several tens of thousands of years ago. Genetic and archaeological evidence shows that humans domesticated wolves on more than one occasion, with the present lineage of the wolf arising at the latest 15,000 years ago as evidenced by the Bonn-Oberkassel site and possibly as early as 33,000 years ago as evidenced by the modern day DNA testing on a Paleolithic dog's remains from the Razboinichya Cave (Altai Mountains). The earliest domesticated dogs have been found that they provided humans with protection, a means to hunt and find food, fur, and a means to carry things long distances. The process continues to this day, with the intentional artificial selection and cross-breeding of dogs to create new breeds of dogs. Some authors wrote as if domestic dogs were descended from a species of now-extinct wild dog distinct from wolves, or from jackals, but that has been disproved.

Lineage

The earliest fossil carnivores that can be linked with some certainty to canids (wolves, foxes and dogs) are the Eocene Miacids some 38 to 56 million years ago. From the Miacids evolved the cat-like (Feloidea) and dog-like (Canoidea) carnivores. The canoid line led from the coyote-sized Mesocyon of the Oligocene (38 to 24 million years ago) to the fox-like Leptocyon and the wolf-like Tomarctus that wandered North America some 10 million years ago.

Canis lepophagus, a small, narrow skulled North American canid of the Miocene era, led to the first true wolves at the end of the Blancan North American Stage such as Canis priscolatrans which evolved into Canis etruscus, then Canis mosbachensis, and in turn Canis mosbachensis evolved to become Canis lupus, the Gray Wolf—immediate precursor to the domestic dogs. The particular subspecies of wolf that gave rise to the various lineages of domesticated dogs has yet to be elucidated, but it is thought that either an undiscovered extinct subspecies or Canis lupus pallipes, the Indian wolf, are the best candidates.

Domestication

How exactly the domestication of the Grey Wolf happened is unclear, but theories include the following:

Orphaned wolf-cubs:

Studies have shown that some wolf pups taken at an early age and reared by humans are easily tamed and socialized. At least one study has demonstrated that adult wolves can be successfully socialized. However, according to other researchers attempts to socialize wolves after the pups reach 21 days of age are very time-consuming and seldom practical or reliable in achieving success.

Many scientists believe that humans adopted orphaned wolf cubs and nursed them alongside human babies. Once these early adoptee’s started breeding among themselves, a new generation of tame "wolf-like" domestic animals would result which would, over generations of time, become more dog-like.

Promise of food/self-domestication:

Early wolves would, as scavengers, be attracted to human field kills and refuse left at human campsites. Dr. Raymond Coppinger of Hampshire (Massachusetts) argues that those wolves that were more successful at interacting with humans would pass these traits on to their offspring, eventually creating wolves with a greater propensity to be domesticated. The "most social and least fearful" wolves were the ones who were kept around the human living areas, helping to breed those traits that are still recognized in dogs today.

Coppinger believes that a behavioural characteristic called "flight distance" was crucial to the transformation from wild wolf to the ancestors of the modern dog. It represents how close an animal will allow humans (or anything else it perceives as dangerous) to get before it runs away. Animals with shorter flight distances will linger, and feed, when humans are close by; this behavioural trait would have been passed on to successive generations, and amplified, creating animals that are increasingly more comfortable around humans. "My argument is that what domesticated—or tame—means is to be able to eat in the presence of human beings. That is the thing that wild wolves can't do."

Furthermore, selection for domesticity had the side effect of selecting genetically related physical characteristics, and behaviour such as barking. Hypothetically, wolves separated into two populations–the village-oriented scavengers and the packs of hunters. The next steps have not been defined, but selective pressure must have been present to sustain the divergence of these populations.

Experimental evidence:

As an experiment in the domestication of wolves, the "farm fox" experiment of Russian scientist Dmitry Belyaev attempted to re-enact how domestication may have occurred. Researchers, working with wild silver foxes selectively bred over 35 generations and 40 years for the sole trait of friendliness to humans, created more dog-like animals. The “domestic are much more friendly to humans and actually seek human attention, but they also show new physical traits that parallel the selection for tameness, even though the physical traits were not originally selected for. They include spotted or black-and-white coats, floppy ears, tails that curl over their backs, the barking vocalization and earlier sexual maturity.

It was reported "On average, the domestic foxes respond to sounds two days earlier and open their eyes one day earlier than their non-domesticated cousins. More striking is that their socialization period has greatly increased. Instead of developing a fear response at 6 weeks of age, the domesticated foxes don't show it until 9 weeks of age or later. The whimpering and tail wagging is a holdover from puppy hood, as are the fore shortened faces and muzzle. Even the new coat colours can be explained by the altered timing of development. One researcher found that the migration of certain melanocytes (which determine colour) was delayed, resulting in a black and white 'star' pattern."

Archaeology

Archaeology has placed the earliest known domestication approximately 30,000 BC, and with certainty at 7,000 BC. Other evidence suggests that dogs were first domesticated in southern East Asia.

Due to the difficulty in assessing the structural differences in bones, the identification of a domestic dog based on cultural evidence is of special value. Perhaps the earliest clear evidence for this domestication is the first dog found buried together with human from 12,000 years ago in Israel and a burial site in Germany called Bonn-Oberkassel with joint human and dog interments dating to 14,000 years ago.

In 2008, re-examination of material excavated from Goyet Cave in Belgium in the late 19th century resulted in the identification of a 31,700 year old dog, a large and powerful animal that ate reindeer, musk oxen and horses. This dog was part of the Aurignacian culture that had produced the art in Chauvet Cave.

33,000-year-old skull of a domesticated canid from Siberia:

In 2010, the remains of a 33,000 year old dog were found in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. DNA analysis published in 2013 affirmed that it was more closely related to modern dogs than to wolves. In 2011, the skeleton of a 26,000 to 27,000 year old dog was found in the Czech Republic. It had been interred with a mammoth bone in its mouth - perhaps to assist its journey in the afterlife.

Domestication of the wolf over time has produced a number of physical or morphological changes. These include: a reduction in overall size; changes in coat colouration and markings; a shorter jaw initially with crowding of the teeth and, later, with the shrinking in size of the teeth; a reduction in brain size and thus in cranial capacity (particularly those areas relating to alertness and sensory processing, necessary in the wild); and the development of a pronounced “stop”, or vertical drop in front of the forehead (brachycephaly). Certain wolf-like behaviours, such as the regurgitation of partially digested food for the young, have also disappeared.

DNA evidence

Before DNA was used, researchers were divided into two schools of thought:

Most supposed that these early dogs were descendants of tamed wolves, which interbred and evolved into a domesticated species.

Other scientists, while believing wolves were the chief contributor, suspected that jackals or coyotes contributed to the dog's ancestry.

Carles Vilà, who has conducted the most extensive study to date, has shown that DNA evidence has ruled out any ancestor canine species except the wolf. Vilà's team analyzed 162 different examples of wolf DNA from 27 populations in Europe, Asia, and North America. These results were compared with DNA from 140 individual dogs from 67 breeds gathered from around the world. Using blood or hair samples, DNA was extracted and genetic distance for mitochondrial DNA was estimated between individuals.

Modern Day DNA evidence suggests that African dogs, such as the Basenji, have a high level of genetic. Based on this DNA evidence, most of the domesticated dogs were found to be members of one of four groups. The largest and most diverse group contains sequences found in the most ancient dog breeds, including the dingo of Australia, the New Guinea Singing Dog, and many modern breeds, like the collie and retriever. Other groups such as the German Shepherd Dog showed a closer relation to wolf sequences than to those of the main dog group, suggesting that such breeds had been produced by crossing dogs with wild wolves. It is also possible that this is evidence that dogs may have been domesticated from wolves on different occasions and at different places. Vilà is still uncertain whether domestication happened once–after which domesticated dogs bred with wolves from time to time–or whether it happened more than once.

A 2002 study by Peter Savolainen identified mitochondrial DNA evidence suggesting a common origin from a single southern East Asian gene pool for all dog populations. In 2010, a study by Bridgett von Holdt, using a larger data set of nuclear markers, pointed to the Middle East as the source of most of the genetic diversity in the domestic dog and a more likely origin of domestication events. Z-L Ding (2011) presented new Y-chromosome data from 151 dogs sampled worldwide, again pointing to a single domestication region south of the Yangtze River. The convergence of modern day DNA and Y-chromosome variability in this region, the authors propose, indicate that a large number of wolves were domesticated, probably several hundred, as part of a sustained cultural practice.

The most puzzling fact of the DNA evidence is that the variability in molecular distance between dogs and wolves seems greater than the 10,000–20,000 years assigned to domestication. Yet the process and economics of domestication by humans only emerged later in this period in any case. Based upon the molecular clock studies conducted, it would seem that dogs separated from the wolf lineage approximately 100,000 years ago. While evidence for fossil dogs lessens considerably beyond 14,000 years ago and ending 33,000 years ago, there are fossils of wolf bones in association with early humans from well beyond 100,000 years ago.

Tamed wolves might have taken up with hunter-gatherers without changing in ways that the fossil record could clearly capture. The influx of new genes from those crossings could very well explain the extraordinarily high number of dog breeds that exist today, the researchers suggest. Dogs have much greater genetic variability than other domesticated animals, such as cats, asserts Vilà.

Once agriculture took hold, dogs would have been selected for different tasks, their wolf-like natures becoming a handicap as they became herders and guards. Molecular biologist Elaine Ostrander is of the view that "When we became an agricultural society, what we needed dogs for changed enormously, and a further and irrevocable division occurred at that point." This may be the point that stands out in the fossil record, when dogs and wolves began to develop noticeably different morphologies.

A 2009 study of African dogs found a high level of DNA diversity. The authors suggest that a new view of the domestication of the dog may be needed. A study by the Kunming Institute of Zoology found that the domestic dog is descended from wolves tamed less than 16,300 years ago south of the Yangtse River in China. An older report said that all dog mitochondrial DNA came from three wild Asian female wolves.

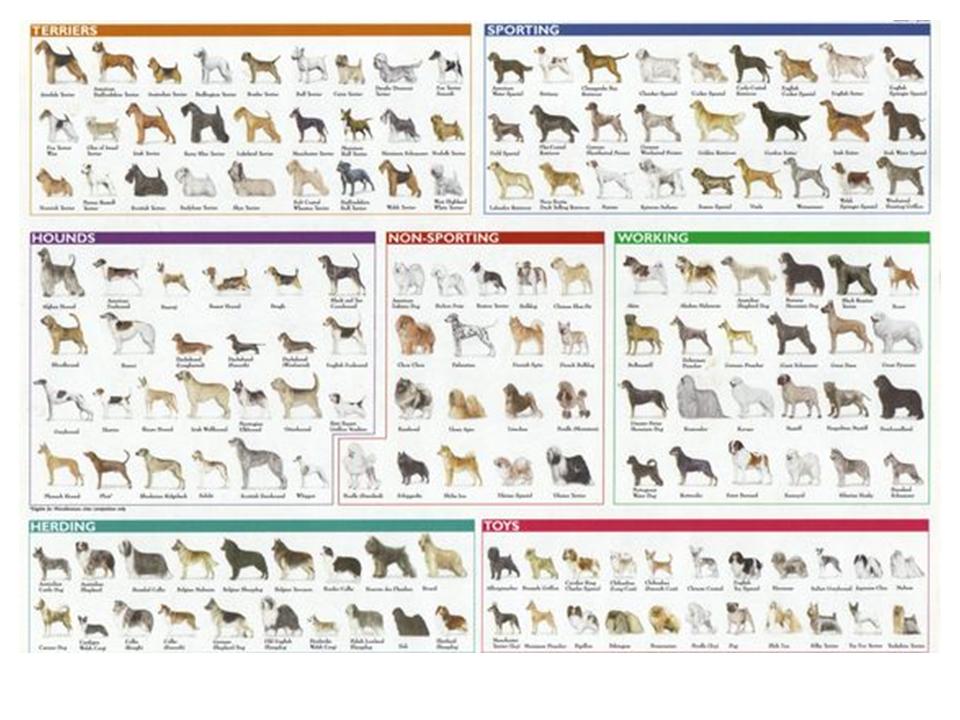

Specialization

As humans migrated around the planet, a variety of dog forms migrated with them. The agricultural revolution and subsequent urban revolution led to an increase in the dog population and a demand for specialization. These circumstances would provide the opportunity for selective breeding to create specialized types of working dogs and pets.

Evolution of diverse dog breeds

This rapid evolution of dogs from wolves is an example of neoteny or paedomorphism. As with many species, young wolves are more social and less dominant than adults; therefore, the selection for these characteristics, whether deliberate or inadvertent, is more likely to result in a simple retention of juvenile characteristics into adulthood than to generate a complex of independent new changes in behaviour. (This is true of many domesticated animals.)

This paedomorphic selection naturally results in retention of juvenile physical characteristics as well. Compared to wolves, many adult dog breeds retain such juvenile characteristics as soft fuzzy fur, round torsos, large heads and eyes, ears that hang down rather than stand erect, etc.; characteristics which are shared by most juvenile mammals, and therefore generally elicit some degree of protective and nurturing behaviour cross-species from most adult mammals, including humans, who term such characteristics "cute" or "appealing". The example of canine neoteny goes even further, in that the various breeds are differently neotenized according to the type of behaviour that was selected.

Herding Dogs:

Herding dogs exhibit the controlled characteristics of hunting dogs. Members of this group, such as Border Collies, Belgian Malinois and German, use tactics of hunter and prey to intimidate and keep control of herds and flocks. Their natural instinct to bring down an animal under their charge is muted by training.

Other members of the group, including Welsh Corgis, Canaan dogs, and Cattle dogs, herd with a more aggressive demeanour (such as biting and nipping at the heels of the animals) and make use of body design to elude the defences of their charges.

Gun Dogs:

Gun dog breeds used in hunting—that is, pointers, setters, spaniels, and retrievers—have an intermediate degree of paedomorphism; they are at the point where they share in the pack's hunting behaviour, but are still in a junior role, not participating in the actual attack. They identify potential prey and freeze into immobility, for instance, but then refrain from stalking the prey as an adult predator would do; this results in the "pointing" behaviour for which such dogs are bred. Similarly, they seize dead or wounded prey and bring it back to the "pack", even though they did not attack it themselves, that is, "retrieving" behaviour.

Their physical characteristics are closer to that of the mature wild canine than the sheepdog breeds, but they typically do not have erect ears, etc.

Scenthounds:

Scenthounds maintain an intermediate body type and behaviour pattern that causes them to actually pursue prey by tracking their scent, but tend to refrain from actual individual attacks in favour of vocally summoning the pack leaders (in this case, humans) to do the job. They often have a characteristic vocalization called a bay. Some examples are the Beagle, Bloodhound, Basset Hound, Coonhound, Dachshund, Fox Hound, Otter Hound, and Harrier.

Sighthounds, who pursue and attack perceived prey on sight, maintain the mature canine size and some features, such as narrow chest and lean bodies, but have largely lost the erect ears of the wolf and thick double layered coats. Some examples are the Afghan Hound, Borzoi, Saluki, Sloughi, Pharaoh Hound, Azawakh, Whippet, and Greyhound.

War/Protection Dogs:

Mastiff-types are large dogs, both tall and massive with barrel-like chests, large bones, and thick skulls. They have traditionally been bred for war, protection, and guardian work.

Bulldog-types are medium sized dogs bred for combat against both wild and domesticated animals. These dogs have a massive, square skull and large bones with an extremely muscular build and broad shoulders.

Terriers similarly have adult aggressive behaviour, famously coupled with a lack of juvenile submission, and display correspondingly adult physical features such as erect ears, although many breeds have also been selected for size and sometimes dwarfed legs to enable them to pursue prey in their burrows.

The least paedomorphic behaviour pattern may be that of the basenji, bred in Africa to hunt alongside humans almost on a peer basis. This breed is often described as highly independent, neither needing nor appreciating a great deal of human attention or nurturing, often described as "catlike" in its behaviour. It too has the body plan of an adult canine predator.

Sled Dogs:

Sled dogs probably evolved in Mongolia between 35,000 and 30,000 years ago. Scientists believe that humans migrated north of the Arctic Circle with their dogs 25,000 years ago, and began using them to pull sleds 3,000 years ago, when hunting and fishing communities were forced north to Siberia by pastoralists. Sled dogs have been used in Canada, Lapland, Greenland, Siberia, Chukotka, Norway, Finland, and Alaska.

Historical references of the dogs and dog harnesses that were used by Native American cultures date back to before European contact. The use of dogs as draft animals was widespread in North America. There were two main kinds of sled dogs; one kind is kept by coastal cultures, and the other kind is kept by interior cultures such as the Athabascan Indians. These interior dogs formed the basis of the Alaskan Husky. Russian traders following the Yukon River inland in the mid-1800s acquired sled dogs from the interior villages along the river. The dogs of this area were reputed to be stronger and better at hauling heavy loads than the native Russian sled dogs.

Of course, dogs in general possess a significant ability to modify their behaviour according to experience, including adapting to the behaviour of humans. This allows them to be trained to behave in a way that is not specifically the most natural to their breed; nevertheless, the accumulated experience of thousands of years shows that some combinations of nature and nurture are quite daunting, for instance, training whippets to guard flocks of sheep.

How Dogs Came To Be Domesticated

At some point in history humans developed close relationships with four-legged creatures that would otherwise been wild, wolves. A study in the journal science argues that the domestic of dogs gapped between 18,800 and 32,100 years ago in Europe. They say that European hunters and gatherers were responsible for turning lupine foes into best friends, long before humans developed agriculture. It’s conclusion that barks up a controversial tree. The study goes against the idea wolves were domesticated when they wandered over to human agricultural settlements, lured by food. The study is also suggesting that dog domestication may have happened in the Middle East or East Asia first.

Researchers extracted and sequenced mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondria are structures in cells that convert food energy into usable forms. When working with these ancient samples, scientists focused on mitochondrial DNA because it is more prevalent in cells than DNA within a cell's nucleus.

Scientists recovered DNA fragments from the genomes of 18 prehistoric dog and wolf-like carnivores and 20 modern wolves with origins in Eurasia and America. Researchers compared these mitochondrial genome sequences with those of 49 wolves, 77 modern dogs, 3 Chinese indigenous dogs and 4 coyotes.

By highlighting similarities in DNA sequences among all of these specimens, researchers put together trees of close relationships called "clades." The more similar two creatures' sequences are, the closer together they will be in the clade.

Researchers organized the specimens in the study into four clades, with three of these groups having sister species represented by ancient fossils from Europe, and the fourth relating to modern wolves as well.

It appears, based on these groupings that the oldest domesticated dogs were in Europe. The carcasses that ancient hunters left behind may have attracted wolves, which could have led to a relationship between dogs and humans.

A group called Clade A includes examples of the modern dog breeds Basenji and Dingo, as well as some pre-Colombian New World dogs as old as 8,500 years. The ancient dogs of the Americas seem to have already been domesticated when they got there, having arrived with humans.

Clade A demographically shows a connection with humans. Between 5,000 and 2,500 years ago dog population declined, but then began to rise sharply starting about 2,500 years ago. Human population size also went up at that time, indicating that dogs were dependent demographically on the human societies. Meanwhile, wolves became scarcer, as agrarian cultures emerged and wolves lost their habitats and wild game. Surprisingly, researchers did not find a population of modern wolves that might have given rise to modern dogs. In fact, modern dogs have more genetically in common with ancient wolves than the ones we see today.

Dogs vs. wolves

Another big surprise from the study is, based on mitochondrial DNA; the two most ancient samples of dog-like creatures included in this study didn't seem to be dogs at all.

One of the oldest samples was previously described in a 2011 study in the journal PLOS One, led by Nikolai Ovodov, a co-author on the new Science study. Ovodov and colleagues described remains of a "dog-like" creature from Razboinichya Cave in Siberia, about 33,000 years old, and found similarities between it and domesticated dogs from Greenland that lived about 1,000 years ago.

But the new study's genetic analysis suggests that this particular sample is an ancient sister lineage to modern dogs and wolves, not a direct ancestor. A 36,000-year-old dog-like carnivore found in Belgium does not seem to represent a direct ancestor either. That’s not something the study authors expected.

It's possible that both of these fossils represent early attempts of humans to domesticate dog-like animals. These creatures did not appear to leave any descendants, so they may signify a failure of domestication.

Alternatively, these creatures may not have been domesticated at all, but rather unusual wolves that died out before the last Ice Age.

More recent specimens -- such as a 14,700-year-old fossil from the Oberkassel site in Bonn, Germany, and the 12,500-year-old fossil from Germany's Karstein cave -- seem to be more directly related to modern dogs. Scientists previously had evidence based on their physical features, but the new mitochondrial genome analysis adds more support.

By 14,000 years ago, "dogs had become a consistent component of human settlements and were subject to deliberate burial themselves and were included in human graves".

On the scent of other theories

This new study doesn't present the whole story, however. It did not include ancient samples from the Middle East or China, which are alternative proposals for the origins of dog domestication. This anticipates that it will be a criticism of the study. Also, regarding wolves, the study included fewer wolf samples from the Middle East and East Asia than other areas, potentially skewing that part of the analysis as well.

But, notes the study's senior author Robert Wayne, a biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, the oldest dog fossils from East Asia are no more than 8,000 years old, making them much younger than the European samples and dating from well after the domestication of dogs. The oldest Middle Eastern dog remains are between 10,000 and 12,000 years old, and so still more recent than the European fossils.

Mitochondrial DNA from ancient canines from these areas would make for a more complete picture of canine evolution, but it was not available in this study. If a 20,000-year-old dog fossil were available from these areas, scientists would also need to find other fossils to arrange them in a tree of relationships. If those were genetically more closely related to modern dogs than the European samples that would argue for a different origin of domestication -- but such samples have not been recovered. This result seems unlikely, given the close associations found between modern dogs and ancient European wolves and dogs.

Many questions remain about the first domesticated canines. They may be dog-gone, but science is making sure they're not forgotten.

©Sled Dog Society of Wales